There is a certain perception out there that traps are traps; that you just put them out there and wait to see what gets caught; and that a trapper will catch any animal that happens to be in the area and is drawn to the trap set. In reality that is far from the truth. Modern trappers are required to be very selective, and there is a wide range of technology and techniques which allow for such selectivity.

While it would be hard to explain in detail without making the post too lengthy, in brief, the type of trap you use, the size trap you use, how you adjust the trap, how you set the trap, where you set the trap, and what bait and lures you use will have a huge impact on what animal you will trap. Much like a hunter carefully selects the weapon he will use for the particular hunt, properly zeroes in the optics, and makes sure they are adequate for the desired shot, a trapper will use the appropriate type and size traps, placed in proper sets, and with proper bait to make sure the target animal is captured. Just like a responsible hunter wouldn’t go black bear hunting with a .22LR rifle, or take a 700 yard shot with iron sights, or go pheasant hunting with a rifle, a responsible trapper would make sure the trap sets are targeted towards the animal he intends to trap.

While accidents can always happen, much of the reports you see from anti-trapping organizations are the result of poor and irresponsible trapping technique, not of trapping itself. For example, there is absolutely no reason why a household cat would ever have its foot caught in a #2 foothold trap (a trap with jaw diameter of 5 1/2 inches designed for coyote, fisher, and larger furbearers). Either the trapper who set the trap did not bother at all to make a proper set, including adjusting the pan tension (the amount of weight you have to place on the trap before it triggers), or the example was staged by an anti-trapping organization for publicity, an act that happens with disturbing regularity.

As I mentioned above, it would be impossible to give a complete tutorial on proper trapping techniques for different animals, nor am I knowledgeable enough to give such a lesson. This post is just intended for those who are not at all familiar with trapping, to get some background on what traps, trap sizes, and basic techniques exist out there to make responsible and selective catches.

So, let’s start with a brief look at the type of traps that are commonly used.

Foothold Traps

Foothold traps have been around for a very long time. The mountain men used them to trap beaver, and they are my preferred way of trapping.

You may have heard these type of traps referred to as leghold traps, but the proper term really is “foothold”. The trap uses two jaws that slide up with the use of springs or arms on the side of the trap, and are designed to catch the animal by the foot. If the trap is catching the animal on the leg, then it is not properly sized for the animal.

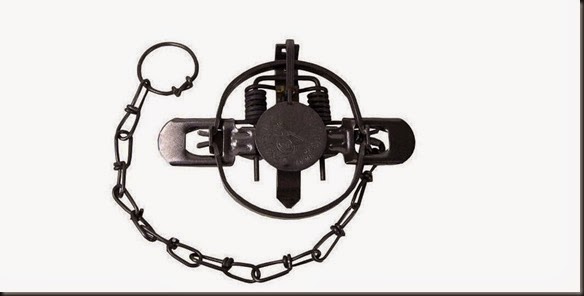

Modern foothold traps use coil springs to push up arms on the side of the trap, which close the jaws. As a result, they are called Coil Spring Traps.

An older version of these traps, but still very effective and in use are the Long Spring Traps. They get their name because instead of coil springs, they use two long springs on the side of the trap to push up the jaws.

Foothold traps come in different sizes, designed for different target animals. Just like you wouldn’t use a rifle chambered in .17HMR to hunt deer, or a rifle chambered in .308 to hunt squirrel, you wouldn’t use a #1 (about 4 inch jaw spread) foothold trap on a wolf or a #4 (about 6 1/4 jaw spread) trap on a mink.

The traps come with different types of jaws, ranging from padded jaws to offset jaws (jaws that leave a gap when closed).

Additionally, on most foothold traps (certainly on the modern ones), you can adjust the pan tension. The pan is the center portion of the trap where the animal has to step in order to trigger it. The pan can be adjusted to be triggered by different weights. So, if you are trapping coyote, you can put a pan tension of about 4 pounds, which would mean that a coyote will trigger the trap, but a lighter animal like a raccoon or mink or household cat will not.

Furthermore, how the trap is set will make a big difference in what animal you catch. Placing the bait the proper distance from the trap to account for the stride of the target animal will make a difference, so will the area where the trap is placed, as well as the bait used. While individually none of these solutions are perfect, combined, a foothold trap can be a very selective devise.

Lastly, there is a common perception that an animal will chew off its leg when caught is such a trap in order to escape. That doesn’t actually happen. A trapped animal will not just pick a spot on its leg above the trap and chew through it in order to get away. What does happen, if a trap is not properly sized is that an animal caught in a trap that is too large, will eventually have the caught part of the foot go numb. At that point the animal starts to treat it as part of the trap rather than it’s own body. If the trap is too large, the animal will be able to get its mouth into the parts of the trap where it’s foot is caught, and in an attempt to bite at the trap, it can bite off that part of its foot. That can be completely avoided by using properly sized traps for the target animal so that it can not get its jaws in the area of the trap where the foot is caught, or by using traps such as stop-loss or double jaw traps which similarly prevent the animal from getting to the area where its foot is held.

A properly sized and set foothold trap will not cause any damage to the animal. After all, these traps were originally designed to make trappers money from the furs they trapped. If the result was compound fractures and torn skin, those trappers would not have been able to make a living.

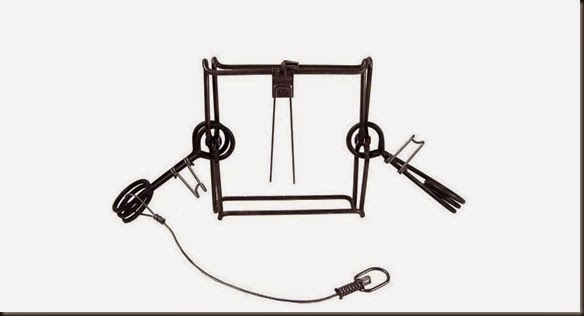

Body Grip Traps (Conibears)

Body grip traps are a more modern innovation. They are sometimes referred to as Conibear traps after their inventor and came about as an attempt to address the concerns people had with the perceived cruelty of foothold traps. In effect, body grip traps are oversized rat traps designed to kill the animal outright when it is caught.

The traps use one or two springs on the side of the jaws to close them when an animal passes through the trap. The jaws are supposed to catch the animal by the neck or spine, killing it instantly.

Just like with foothold traps, body grip traps come in different sizes. Manufacturers use different designations, but in general terms a 110 body grip trap will have a jaw span of about 4 1/2 inches, and be designed to catch mink and muskrat, a 220 will have a jaw spread of about 7 inches and be intended for raccoon and similarly sized animals, a 330 will have a jaw spread of about 10 inches and be designed primarily for beaver and otter. There are sizes and variations in between, and each manufacturer has slightly different sizing. A responsible trapper will use the appropriate trap size for the target animal. The same way you wouldn’t hunt turkey with 1oz #8 shot shells, you wouldn’t trap raccoon with a 110 body grip trap.

Body grip traps are generally ineffective on canines and cats because they are unwilling to stick their heads through the trap.

Just like with foothold traps, using the proper size trap is important, and it’s even more important with body grip traps where the goal is to instantly kill the animal. If the trap is too small for the animal you are targeting, it may not kill it.

Here as well, the way the trap is set makes a difference. For example, while you can bait the trap directly as you would with a rat trap, that can lead to unintended catches like birds. That can be avoided by placing the bait away from the trap, requiring that the animal walk through it before it can get caught. Similarly, placing the trap on a leaning pole will preclude canines from being caught as they usually will not climb up a tree.

Other tricks like offsetting the trigger to one side can allow smaller animals to pass through while still catching the intended furbearer.

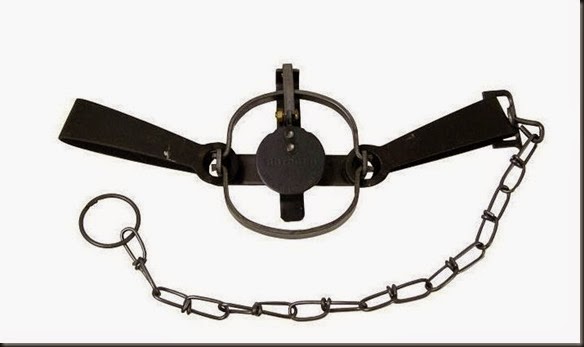

Dog Proof Traps

Dog proof traps are specifically designed raccoon traps that will not catch dogs. They are a specialized trap that gets used a lot in residential areas where raccoons can be a problem, but there are also a lot of domestic dogs.

The trap works as a foothold trap, but prevents dogs from being caught because it requires that the animal stick its paw inside the trap. Raccoons have opposing thumbs and will reach into holes to get the bait, while a dog will not. They are a very effective trap, and are a good tool when trapping needs to be done in populated areas.

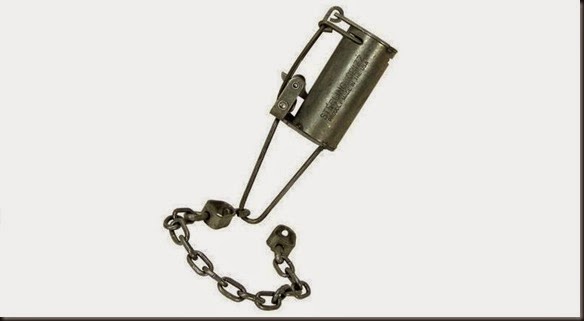

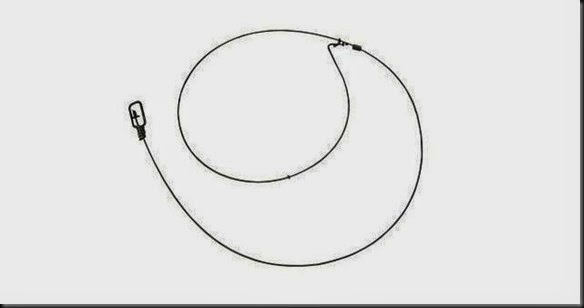

Snares

Snares are one of the oldest methods for trapping. They work by getting an animal to walk through a noose, and tighten it when the animal pulls away.

Many states don’t allow snares. My state does not, so I don’t have experience with using them. As such I can’t give you many details or personal observations on their use.

Modern snares do incorporate safety features designed to avoid non target animals. Brake-away links and locks can increase the chance of an effective kill or the release larger non target animals such as a deer that might have gotten its foot caught in the snare.

Snares are rarely seen on trap lines (at least from what I’ve beet told by people who trap where snaring is allowed) because they are not very cost effective. They get easily damaged, and if you plan on running a line all season, replacing them can get costly.

Cage Traps

The last type of trap that is used with some frequency is the cage trap. As the name indicates, the traps work by catching the animal within a cage.

These traps can be very effective on some animals like woodchuck, and not others. They are generally used in residential areas where a particular animal has to be captured. Running a full trap line with cage traps would not be desirable, even if possible, just because of the size of each trap.

The benefit of cage traps is that they do not harm the animal in any way, so in residential areas where the land owners are worried about numerous pets running around, cage traps are a good option.

The above is just a quick run down of the most popular traps used, and some general background on the methods and technology utilized by responsible trappers to assure proper catches. When done correctly, a trapper will be just as selective about his gear, tools and techniques as a responsible hunter, to make sure that the equipment is properly designed for the targeted animal, and that the techniques employed will protect non-target wildlife.

State regulations further ensure proper catches. Many limit trap sizes that can be used, how the triggers must be set, or how the traps can be placed. Just as an example, in NY State I can use 220 body grip traps, but I must set them at least 4 feet above the ground or in box containers with limited openings. That regulation is designed to avoid the capture of dogs. Similarly because our otter season is shorter than our beaver season, when using 330 body grip traps for beaver outside of otter season, the trigger has to be offset to allow otters to pass through while still being triggered by beaver.

There are many, many technical aspects of the trap designs and their use which trappers utilize and take into consideration. Many even modify their own traps to make them more effective. In later posts I will try to address some of the specifics.

No comments:

Post a Comment